Fish Cleaning Tutorial: A Complete Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners

Ever brought home a fresh catch and felt unsure how to prepare it? This complete fish cleaning tutorial walks you through the entire process, from scaling and gutting to filleting, with essential safety tips and tool recommendations for perfect results every time.

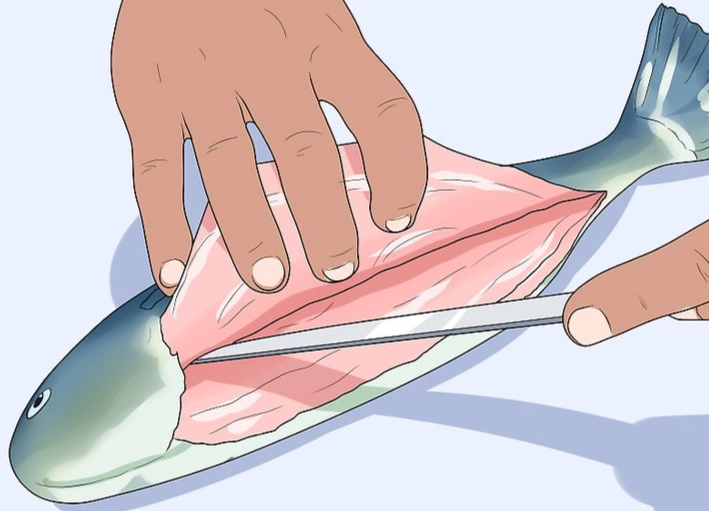

Let's be honest. The first time I had to clean a fish I caught, it was a disaster. I had a dull pocket knife, a plastic bag for a cutting board, and zero clue. The fish ended up looking like it lost a fight with a lawnmower, and I wasted a lot of good meat. Sound familiar? If you're staring at a beautiful fresh catch—whether from the lake, the market, or a friend's lucky day—and feel that mix of excitement and dread, you're in the right place. This isn't just another dry list of steps. This fish cleaning tutorial is the one I wish I had, born from my own messy mistakes and years of figuring out what actually works. Why bother learning this, anyway? Well, beyond the obvious pride of doing it yourself, a properly cleaned fish tastes noticeably better. You remove the parts that cause bitterness and spoilage faster. You get more usable meat. And you connect with your food in a way that plastic-wrapped fillets from a store just can't match. It's a fundamental skill for any angler or home cook serious about seafood. Jumping right in with a knife is the biggest mistake. The prep work is what separates a stressful mess from a smooth, almost meditative process. Think of it like setting up your workshop. You don't need a fancy, expensive kit. But using the right tool for the job is a game-changer. Here’s my breakdown, from absolute essentials to nice-to-haves. The Non-Negotiables: A sharp fillet knife (a flexible 6-inch blade is perfect for most fish), a cutting board (plastic is easier to sanitize, wood looks nicer), a trash bag or bowl for guts, a hose or large bowl of clean water, and paper towels. That's your core kit. A dull knife is dangerous—it slips. I learned that the hard way with a minor but memorable cut. The Game Changers: A fish scaler (a spoon works in a pinch, but a proper scaler is faster), a pair of needle-nose pliers (for pulling pin bones—trust me), and a dedicated pair of kitchen shears. If you're dealing with fish like catfish or monkfish, a strong pair of gloves is wise. And then there's the cutting surface. A stable, non-slip surface is crucial. I once used a wobbly picnic table and nearly sent the fish flying. Not ideal. You can dampen a towel and put it under your board for extra grip. This part gets glossed over in most guides. Fish are slippery. Knives are sharp. It's a combo that demands respect. Rule #1: Cut Away From You, Always. Your fingers should be curled under, using your knuckles as a guide for the knife. If the blade slips, it goes into the board or empty space, not your hand. The U.S. Coast Guard's Boating Safety Resource Center has good general tips on safe knife handling that apply perfectly here. It's basic, but it prevents trips to the ER. Wet a paper towel and put it under your cutting board. It stops the board from sliding around like it's on ice. Keep your workspace clean. Fish slime and water make everything slippery. Have a dedicated “gut bowl” so you're not reaching over a messy pile. And for heaven's sake, if you're outside, be aware of flies. They appear out of nowhere the moment you make the first incision. Okay. Tools are laid out. Board is secure. Knife is sharp. You're mentally ready. The fish is rinsed and staring at you. Now, the real work of this fish cleaning tutorial begins. We'll follow the logical flow: from whole fish to ready-to-cook portions. I'm going to break this down into phases. You might not need all phases (like scaling a fish you're going to skin), but understanding the sequence is key. This is the most ethical and quality-focused start, especially for a fish you've just caught. A quick, humane stun results in less stress hormones in the meat and an easier process for you. For a just-caught fish: A firm, sharp blow to the top of the head, just behind the eyes, with a priest (a weighted tool) or the blunt back of a heavy knife will render it insensible immediately. It feels harsh to write, but it's far kinder than letting it suffocate in a cooler. Next, bleeding. This is the secret for pristine, white, odor-free fillets. Make a deep cut across the throat, just behind the gill plate and below the pectoral fins, severing the main arteries. Rinse it under cold water or place it in a bucket of water for a few minutes. The water will run clear. This step removes the blood that can cause a metallic, “fishy” taste and speeds up the cooling process. I skip this sometimes when I'm in a hurry, and I always regret it. The fillets are just darker and have a stronger smell. Do you need to scale? If you're planning to eat the skin (like on a pan-seared trout or snapper), yes. If you're going to remove the skin entirely (common with cod, haddock), you can skip it. Check your recipe. Lay the fish on its side. Hold it firmly by the tail. Using a fish scaler or the back of a knife, scrape from the tail towards the head. Scales fly everywhere. Do this outside, in a deep sink, or inside a large plastic bag to contain the mess. Apply firm, short strokes. Pay extra attention near the fins, head, and the lateral line (the stripe along the side). Rinse thoroughly. Missed scales are like little pieces of plastic in your food—not pleasant. This is the core of any fish cleaning tutorial. The goal is to remove all the internal organs without puncturing the guts or the bitter-tasting gall bladder. Gall Bladder Watch: The gall bladder is a small, greenish sac attached to the liver. If you nick it, it releases an intensely bitter liquid that can ruin the meat. If it breaks, immediately rinse the area thoroughly with water and consider rubbing with salt or lemon juice to mitigate the taste. It's not the end of the world, but try to avoid it. Some people remove the gills at this point with shears, as they can also harbor bacteria and cause off-flavors. I usually do, especially if I'm storing the whole gutted fish for a day. Now you have a clean, whole fish. The next step depends on how you want to cook it. Option A: Filleting (Boneless Cuts) Option B: Steaks (Cross-Section Cuts) Option C: Pan-Dressing (Butterflying) Some recipes call for skinless fish. Here's the trick: start at the tail end. Place the fillet skin-side down on the board, tail facing you. Grab the tail end of the skin firmly with your fingers or a paper towel for grip. Angle your knife blade almost flat against the board (about 10-15 degrees) and use a gentle sawing motion to separate the meat from the skin. You're essentially sliding the knife between the skin and the flesh. The key is that back-and-forth motion and keeping the blade almost parallel to the board. Pull the skin taut as you go. Even in a fillet, you'll feel a line of tiny, needle-like bones running down the center. These are pin bones. Run your fingers along the fillet—you'll feel them. Take your clean needle-nose pliers, grab the tip of each bone firmly, and pull it out in the direction it's pointing (usually towards the head). It's satisfying work. Some people use dedicated fish bone tweezers, but my garage pliers work just fine after a good wash. Not all fish are created equal. A one-size-fits-all approach fails here. This table sums up the quirks of common types. You have beautiful fillets or a clean whole fish. Now what? Improper storage ruins all your hard work. Cleanup: Don't procrastinate. Wash your knives, board, and tools with hot, soapy water immediately. A little white vinegar can help cut the fishy smell. Dispose of the guts, scales, and head promptly—either bury them deep in a garden (great fertilizer), seal them in a bag for trash, or if you're by the water and regulations allow, return them to the ecosystem (away from swimming areas). Leaving them in your outdoor trash can for days is a recipe for attracting every raccoon in the county. Look, the first few times you follow a fish cleaning tutorial, it will feel awkward and slow. You might make a few ugly cuts. You might leave a few scales. That's okay. I still occasionally mess up a fillet, especially on a new species. The point is to start. Grab a few inexpensive, small fish from the market and practice. The muscle memory will come. The real reward comes later. When you sit down to a meal of fish you caught, cleaned, and cooked yourself, the flavor is different. It's the taste of accomplishment, of knowing a fundamental skill, and of respecting the whole ingredient. It connects you to your food in a real way. And honestly, it saves you money—whole fish are almost always cheaper per pound than pre-cut fillets. So, take a deep breath, sharpen that knife, and give it a go. Use this guide as your reference. Bookmark it. Come back to it. And remember, every expert was once a beginner who decided to make the first cut. Got a specific fish you're struggling with? The process might seem daunting, but by breaking it down into these phases—setup, scaling, gutting, portioning, finishing—you take control of what feels like a chaotic task. This fish cleaning tutorial aimed to demystify each of those phases. Now, the only thing left to do is try it for yourself.Quick Guide

--- Let's get our hands (metaphorically) dirty. ---

--- Let's get our hands (metaphorically) dirty. ---Before You Make the First Cut: The Mental and Physical Setup

Gathering Your Arsenal: The Tool Rundown

The Mindset & Safety Stuff (Boring but Critical)

The Step-by-Step Fish Cleaning Tutorial: From Whole Fish to Dinner

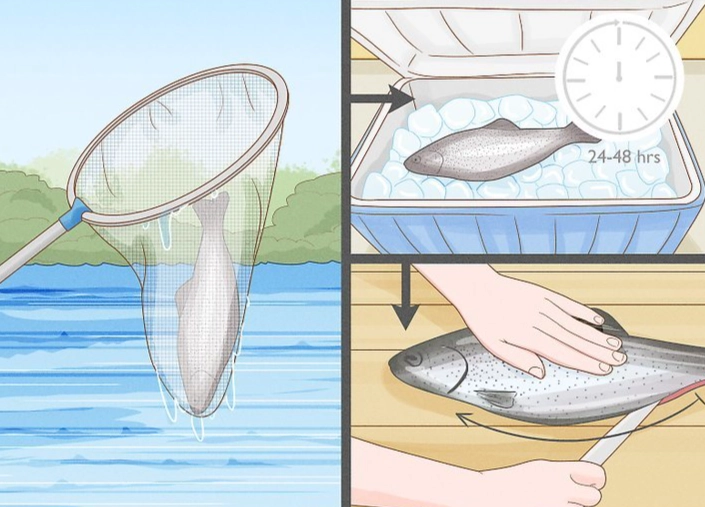

Phase 1: The Preliminary Steps (Stunning & Bleeding)

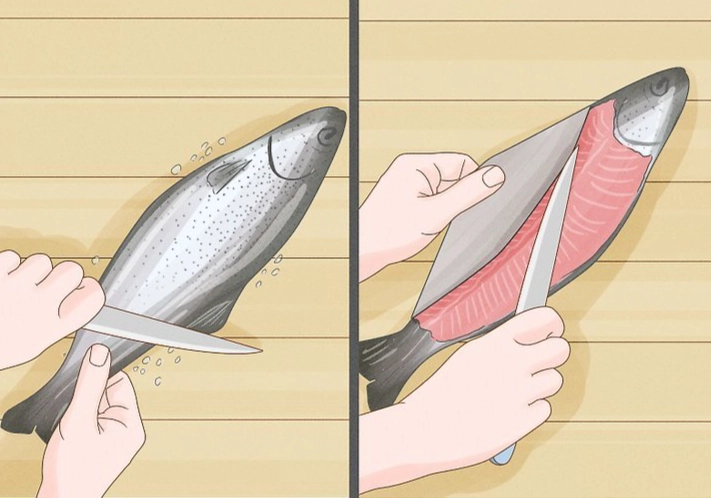

Phase 2: Descaling (If Needed)

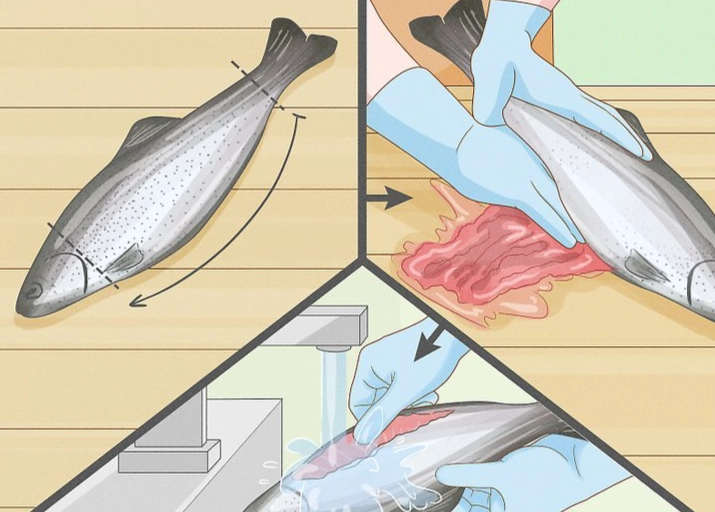

Phase 3: Gutting (The Main Event)

Phase 4: From Gutted Fish to Fillets or Steaks

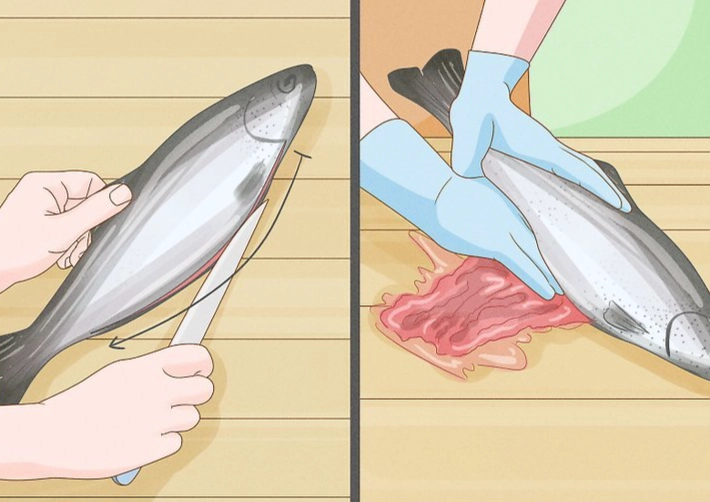

This is the most popular goal. The idea is to remove the meat from the bones in two clean pieces.

Better for large, round fish like salmon, tuna, or swordfish. Simply cut the gutted fish crosswise into 1-inch to 1.5-inch thick slices, starting just behind the head. You'll get a center bone piece in each steak. Use a heavy, sharp chef's knife or a cleaver for a clean cut.

Perfect for medium-sized fish like trout or branzino. After gutting, make a cut along the backbone from the inside, opening the fish like a book. You can remove the backbone entirely or leave it in. This creates a flat, beautiful piece that's great for grilling or baking.Phase 5: Skinning a Fillet

Phase 6: The Final Touch – Pin Bone Removal

Beyond the Basics: Handling Different Fish Types

Fish Type

Common Examples

Key Challenge in Cleaning

Pro Tip & Recommended Method

Small, Bony Fish

Panfish (Bluegill, Perch), Smelt

Lots of small bones, not much meat for filleting.

Often best pan-dressed (scaled, gutted, head removed). Frying crispifies the small bones. Scaling is a must.

Round, White Fish

Cod, Haddock, Pollock, Snapper

Thick rib cage, delicate flesh that can tear.

Perfect for filleting and skinning. Use a very sharp, flexible knife. Skin is often removed. Pin bones are prominent.

Oily, Robust Fish

Salmon, Trout, Mackerel

Tough scales, strong bloodline, thick skin.

Scale thoroughly (salmon scales are tough!). Bleeding is crucial for mild flavor. Skin is often left on for cooking. Great for steaks or fillets.

Flatfish

Flounder, Halibut, Sole

Weird anatomy (both eyes on top), four fillets not two.

Fillet from the top (dark side) first, then the bottom (white side). You'll get two smaller fillets from each side. The skeleton is a great guide.

Armored Fish

Catfish, Sturgeon

Skin is like sandpaper (catfish) or has bony plates (sturgeon).

Skinning is mandatory, not optional. For catfish, make a cut around the head, peel the skin off with pliers in one piece—it's oddly satisfying. Wear gloves.

What Comes After the Knife Work: Storage & Cleanup

The goal of this fish cleaning tutorial isn't just to get you through the process once. It's to give you the confidence to do it again, better and faster each time, until it becomes second nature.

Answers to the Questions You're Probably Asking (FAQ)

Wrapping Up This Fish Cleaning Tutorial Journey