The Complete Guide to Fishing Sonar: How to Choose & Use Fish Finders Like a Pro

Ever wondered how fishing sonar actually works and how to pick the right one? This ultimate guide breaks down everything from basic principles to advanced techniques like CHIRP and LiveScope, helping you find more fish and understand your underwater world.

Let's be honest. For years, I thought a fishing sonar was just a fancy screen that showed fish icons. I'd see guys with these massive units on their boats, staring intently at colorful displays, and I figured it was mostly for show. Maybe it helped a little, but how complicated could it be? Sound goes down, bounces off stuff, and shows you a picture. Right? Then I spent a day on the water with a guide who really knew his stuff. He wasn't just looking for fish; he was reading the bottom composition like a map, identifying specific weed lines, pinpointing rock piles he'd never seen before, and even distinguishing between a school of baitfish and a lazy walleye hugging the bottom. My mind was blown. That screen wasn't just showing fish; it was revealing an entire hidden world. I was fishing blind before that. That's what this guide is about. I'm not going to just list specs and models. I want to help you understand how fishing sonar technology actually works, cut through the marketing jargon, and figure out how to use it to catch more fish. Whether you're in a kayak or a bass boat, there's a fish finder that can change your game. Forget the complex physics. At its heart, a fish finder is an echo-locator. The unit on your boat (the display) sends an electrical signal to a transducer hanging in the water. This transducer is the magic piece—it converts that signal into a sound wave (a *ping*) and shoots it down into the depths. Sound travels through water way better than light. When that sound wave hits something—the bottom, a tree stump, a fish's swim bladder—it bounces back. The transducer catches this returning echo and converts it back into an electrical signal for the display. The key thing is timing. The unit measures how long it took for the echo to return. A quick return means the object is shallow (like a fish near the surface). A long return means it's deep (like the lake bottom). The display paints a picture based on the strength and timing of millions of these pings. A hard, rocky bottom returns a strong signal and shows up as a thick, dark line. Soft mud returns a weaker signal and looks thinner or fuzzier. A fish's air-filled swim bladder is a great reflector, so it shows up as an arch (more on that later) or a blob. It's simple in theory, but the devil—and the magic—is in the details of how those sound waves are created and interpreted. That's where all the different technologies like CHIRP, Side Imaging, and LiveScope come into play. This is where most people's eyes glaze over. 2D, CHIRP, Down Imaging, Side Imaging, LiveScope, 360 Imaging... what does it all mean, and what do you actually need? Let's break them down one by one. This is your classic, bread-and-butter sonar view. It shows you a vertical slice of the water directly below your boat. For decades, this was the standard. You'd see the bottom line, and fish would appear as arches (if you were moving) or blobs (if you were still). Then came CHIRP (Compressed High-Intensity Radiated Pulse). This wasn't just a minor upgrade; it was a game-changer. Instead of sending out a single frequency *ping*, CHIRP sends a sweeping range of frequencies (like a bird's chirp, hence the name). This returning signal contains way more data. The result? Incredibly detailed target separation. On a traditional sonar, two fish close together might look like one big blob. With a good CHIRP unit, you can often see them as two distinct arches. It also does a much better job of distinguishing between a small fish and a piece of debris. Most modern fish finders worth their salt use some form of CHIRP. It's become the new baseline for clear, readable 2D sonar. This is where things get visually spectacular. Instead of just looking straight down, these technologies use specialized transducers to look out to the sides or directly beneath with a fan-shaped beam. Side Imaging shoots beams out to the left and right of your boat, creating a detailed, almost photographic, view of the bottom structure hundreds of feet away. It's phenomenal for scouting. You can cruise over an area and map out long stretches of river channel, identify isolated brush piles, find submerged roadbeds, or locate the perfect dock. It's not as good for watching your lure in real-time directly below you, but for finding where the fish *might* be, it's unmatched. The first time I used side imaging to find a sunken boat hull full of bass, I felt like I had superpowers. Down Imaging is similar but focuses the beam in a narrow, downward-facing fan. It provides a super-clear, detailed picture of what's directly under your boat. Think of it as a high-definition version of the traditional 2D view. It's great for seeing the exact shape of a stump, the density of weeds, or the composition of the bottom (rocks vs. sand) with stunning clarity. Most units now bundle these together. You'll often run a split-screen with 2D CHIRP on one side and Down Imaging on the other, getting the best of both worlds. If side imaging was superpowers, this is witchcraft. LiveScope (Garmin's brand name), ActiveTarget (Humminbird), and LiveSight (Lowrance) are forms of real-time, scanning sonar. The transducer constantly rotates or scans, updating the display many times per second. The result is a live, lag-free video feed of what's happening around your bait. You can see your jig falling on the screen. You can watch a bass swim up from a brush pile, inspect your lure, and turn away (heartbreaking, but informative!). You can cast to a specific fish you see holding on the edge of a drop-off. It's fundamentally changed techniques like vertical jigging and finesse fishing. The downside? Price. The units and specialized transducers are a significant investment. And some argue it takes some of the mystery—and therefore the sport—out of fishing. I get that, but as a tool for understanding fish behavior, it's incredible. You can learn more about the practical applications of this tech from experts at Bassmaster, who often feature it in tournament coverage. Walking into a store or browsing online can be overwhelming. Screens from 4 inches to 12 inches, bundles with different transducers, prices from $100 to over $3000. Let's talk about what actually matters for your fishing. My first mistake was buying a super basic unit because it was cheap. I quickly outgrew it. The screen was tiny, it had no mapping, and the sonar image was fuzzy. I ended up selling it at a loss and buying a mid-range unit a year later. Sometimes, spending a bit more upfront saves money and frustration. Screen Size & Resolution: Bigger and sharper is almost always better, especially if you want to run split-screens. A 7-inch screen is a great sweet spot for most boats. For kayaks, 5-7 inches is manageable. Don't just go by diagonal size—check the pixel count (e.g., 800x480 vs. 1024x600). Higher resolution means crisper details on side imaging and maps. Transducer: This is the heart of the system! The unit on the display is just the brain. The transducer does the sensing. Most mid-range combos come with a transducer that does CHIRP 2D and Down/Side Imaging. Check what's included. If you want LiveScope-style sonar, you'll almost always need to buy a separate, specific transducer. Mapping & GPS: This is non-negotiable for me now. A built-in GPS lets you mark waypoints ("Fish Here!"), create routes, and most importantly, use lake maps. Preloaded maps or compatibility with detailed contour maps (like LakeMaster or Navionics) is a massive advantage. You can study depth contours at home and identify potential spots before you even hit the water. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) provides foundational data that many commercial mapmakers use, especially for topography and water data. Power (Watts RMS): More power means a stronger signal that can penetrate deeper water and provide clearer returns in rough conditions. For deep-water fishing (over 100 feet), you want higher power (500W+). For shallow water, lower power is fine and is easier on your battery. You can buy the best fish finder in the world, but if the transducer is mounted poorly, it'll perform terribly. The key principle: the transducer needs a clean, bubble-free flow of water across its face. Transom Mount (Most Common): This is the bracket on the back of your boat. The transducer should be mounted on the side that doesn't get turbulent water from the propeller (usually the starboard/right side). It must be level side-to-side and front-to-back. When the boat is on plane, the transducer should still be in the water. Too high, and you'll lose signal at speed. Too low, and it creates drag and can catch weeds. Follow the manual's height guidelines precisely. I learned this the hard way with a unit that would "blink out" every time I went fast. Through-Hull & In-Hull: More permanent, cleaner installations for fiberglass boats. Through-hull requires drilling a hole (best left to pros). In-hull involves epoxying the transducer inside the hull, shooting through the fiberglass. This works surprisingly well on solid hulls but causes some signal loss. Trolling Motor Mount: Popular for bass anglers. A bracket attaches the transducer to the lower unit of the trolling motor. This gives you great control—you can point your sonar beam exactly where you're casting. Just watch for snags in heavy cover. Once it's physically installed, spend time on the water adjusting the settings. Don't just leave it on "Auto" mode forever. For proper installation standards and electrical considerations, especially on larger vessels, it's wise to reference guidelines from organizations like the National Marine Electronics Association (NMEA). They set the standards for data connectivity between marine electronics. This is the art form. The machine gives you data; you have to interpret it. Fish Arches: The classic fish symbol. An arch is created when a fish swims through the cone-shaped beam of a 2D sonar. As it enters the edge of the cone, the signal is weak (start of the arch). When it's directly under the transducer in the center of the cone, the signal is strongest (top of the arch). As it leaves the other side, the signal weakens again (end of the arch). If you're stationary, a fish hanging in the beam will just show as a solid line or blob. No arch. Bottom Hardness: A thin, sharp, dark bottom line usually means hard bottom (rock, clay). A thick, wider, lighter-gray or fuzzy bottom line suggests soft bottom (mud, silt). Weeds & Structure: On 2D, weeds often look like fuzzy, upward-reaching lines or clouds from the bottom. On Down Imaging, they look much more realistic—you can see individual stalks. Trees look like, well, trees. Brush piles are chaotic clusters. Baitfish: Usually appears as a dense cloud or a large, indistinct blob of tiny dots. Individual baitfish are too small to show up clearly unless they're in a massive ball. The single best thing you can do is practice. Drop a marker buoy over something you see on the screen. Then, use your camera (if you have one) or even a heavy jig to physically feel what's down there. Correlate the feel with the image. "Oh, that thick fuzzy line *is* soft mud. That thin dark line *is* a rocky ledge." This is a hot debate. The scientific consensus, from studies by fisheries agencies, suggests that the frequency ranges used by recreational fish finders are generally outside the sensitive hearing range of most game fish. They might detect it as a distant background noise, but it's unlikely to spook them like a boat shadow or a loud bang would. I've caught plenty of fish directly under my transducer. Don't worry about it. Set your range to cover both sides, maybe 80-120 feet each side depending on water depth. Cruise along contours (like a drop-off or a river channel edge) at a moderate speed (3-5 mph). Look for anomalies: a single hard spot (rock) on a soft bottom, a dark shadow extending from the bottom (standing timber), or a bright, irregular return (a pile of rocks or a wreck). When you see something promising, mark it with a waypoint immediately! Then, circle back and hover over it with your 2D or Down Imaging to investigate further. It's not just for watching fish eat. Its real power is in searching. You can sit off a point, scan the area in front of you 100+ feet out, and see if any fish are suspended off the end or holding on the side. It eliminates blind casting. The learning curve is steep—interpreting the live, jittery image takes practice. Start by just watching your lure fall to get used to the perspective. You probably need to adjust your sensitivity/gain (turn it down) and your surface clutter/noise rejection filters (turn them up a bit). Also, check your transducer for tiny air bubbles or debris. A piece of grass stuck to it will ruin your picture. Almost all modern fishing sonar units have built-in GPS. It's essential. The ability to mark a "honey hole" and return to the exact spot next week is priceless. The integration of mapping and sonar on one screen is the modern standard. For in-depth, trustworthy reviews of specific models before you buy, I always cross-reference with hands-on tests from reputable sources like Sport Fishing Magazine or dedicated electronics experts on YouTube who show real on-water performance. Choosing and using a fishing sonar isn't about buying the most expensive gadget. It's about choosing the right tool to answer the questions you have about the water you fish. Start with the fundamentals: a good CHIRP 2D sonar with GPS mapping. Learn to read it inside and out. Understand what the bottom tells you, how fish appear, and how your speed affects the image. Once you've mastered that, then consider adding layers like Side Imaging for scouting or, if you're really curious (and your budget allows), dipping a toe into the real-time sonar world. Each piece of technology is a lens into the underwater world. The more lenses you learn to use, the clearer the whole picture becomes. Remember, the fish finder doesn't catch fish. You do. It just gives you the information to make smarter decisions, waste less time, and understand the environment you're fishing in. And that, in my opinion, makes the whole sport more interesting and rewarding. Now get out there, ping away, and see what you've been missing.In This Guide

How Does a Fishing Sonar Actually Work? (No PhD Required)

Navigating the Alphabet Soup: Types of Sonar Technology

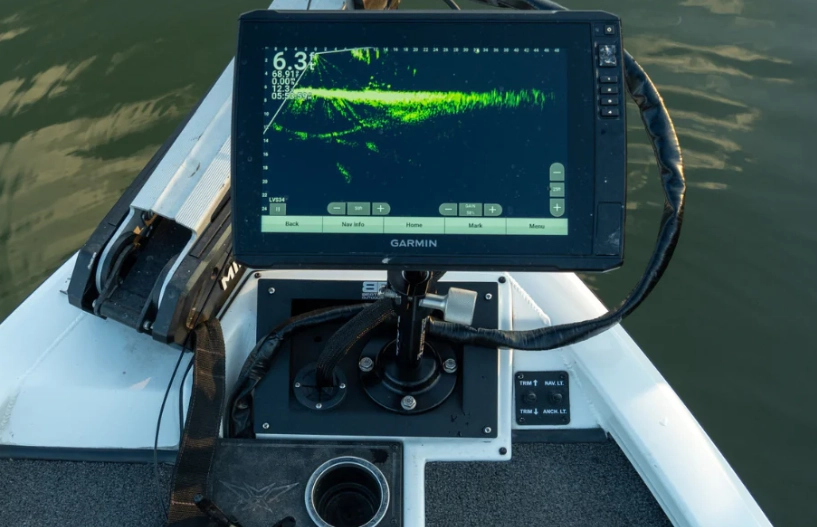

The Workhorse: Traditional 2D & CHIRP Sonar

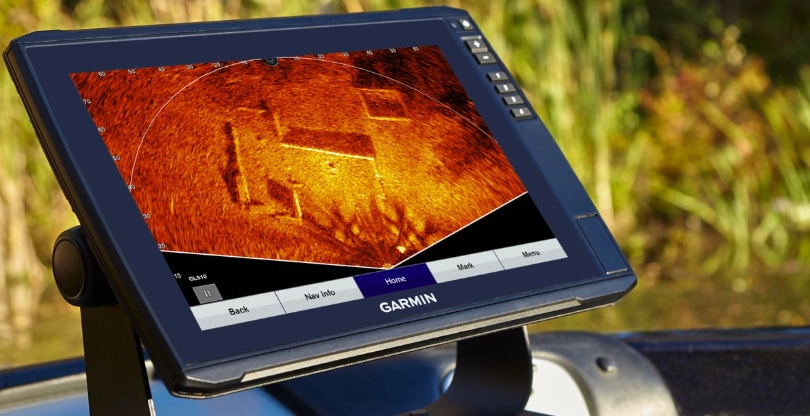

Seeing to the Sides: Side Imaging & Down Imaging

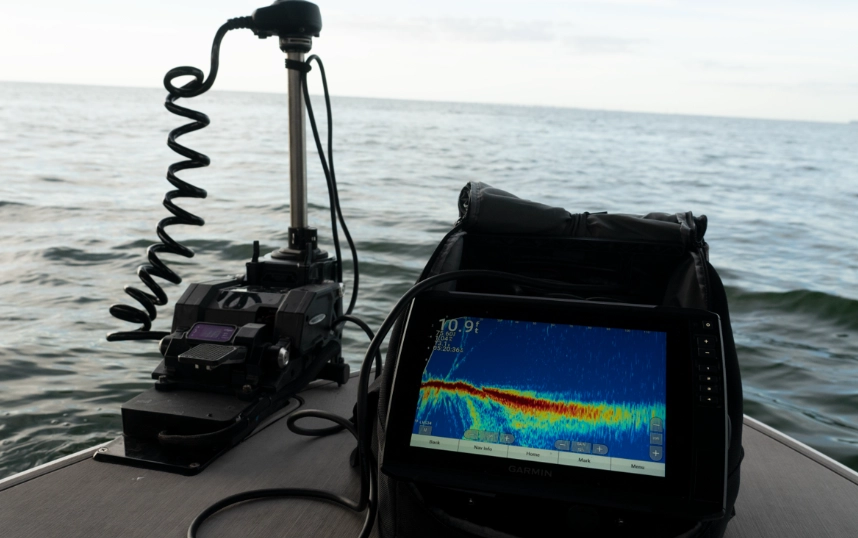

The Game Changers: LiveScope & Real-Time Sonar

Technology

Best For

Visual Style

Key Limitation

2D CHIRP Sonar

Depth finding, basic fish arches, water temperature, overall versatility.

Vertical scroll, classic arches.

Limited detail on bottom composition/structure.

Down Imaging

Seeing detailed structure directly below (stumps, rocks, weeds).

High-definition picture of the bottom.

Limited horizontal coverage; narrow view.

Side Imaging

Scouting and mapping large areas, finding isolated cover.

Top-down, map-like view of sides.

Poor for watching lures in real-time directly below.

Live Sonar (e.g., LiveScope)

Real-time bait tracking, seeing fish react, vertical fishing.

Live video-like feed.

Very high cost, steep learning curve, can be overwhelming.

Choosing Your Fishing Sonar: A Practical Buyer's Guide

First, Ask Yourself These Questions:

Key Features to Compare

Brand (Examples)

Common Strengths

Things to Consider

Best For Anglers Who...

Garmin

Pioneered LiveScope, user-friendly interfaces, great touchscreens.

Their ecosystem can be pricey to get into fully.

Want cutting-edge real-time sonar and intuitive operation.

Humminbird

Deep integration with Minn Kota trolling motors (i-Pilot Link), strong mapping (LakeMaster).

Some find menus less intuitive. ActiveTarget is their real-time answer.

Use Minn Kota motors and value integrated boat control.

Lowrance

Long history, respected 2D sonar, strong saltwater offerings, LiveSight.

Interface can feel more "techie" or dated to some.

Are traditionalists, fish saltwater, or like a more data-driven approach.

Raymarine

Excellent for sailboats and larger vessels, great in saltwater.

Smaller market share in freshwater fishing.

Have dual fishing/boating needs or are on bigger water.

Installation & Setup: Don't Screw This Up

Reading the Screen: From Blobs to Fish

Advanced Techniques & FAQs

Does sonar scare fish?

How do I use side imaging to find new spots?

What's the deal with forward-facing sonar (like LiveScope)?

My screen is a mess of clutter. Help!

Do I need a separate GPS unit?

Wrapping It Up: Your Sonar Journey